About the author

The early years. Pablo Picasso reportedly said: Every child is an artist; the difficulty is to remain one as we grow. This was certainly true for me. In the mid-1950s, around age ten, I felt I was not good enough at art. So, I gave up and stopped drawing … a choice I’ve come to regret.

Since this statement is about being an artist, I will give only brief mention to the next sixty years that were filled with other passions: the love of a wonderful life partner; helping her raise our two artistically talented sons; our self-reliant lifestyle on an old Vermont farmstead; living and working for periods in Europe and especially Africa; traveling through some 80 countries; gardening, for both food and beauty; and hardscaping terraces and waterfalls, among other memorable highlights. I had a great life.

Return to art. At age 70 I found myself widowed, retired, out of Africa, living alone in a cabin in the woods, and seriously in need of a new passion. Art came to my rescue. I bravely signed up for a workshop on sketching portraits. With expectations greatly reduced from those of my juvenile self, I quickly became hooked on that magical moment when marks on paper somehow coalesce into a recognizable image. Portraits became my preoccupation, sketching into the night, so curious to see each face materialize, and so keen to improve, to get ‘good enough’.

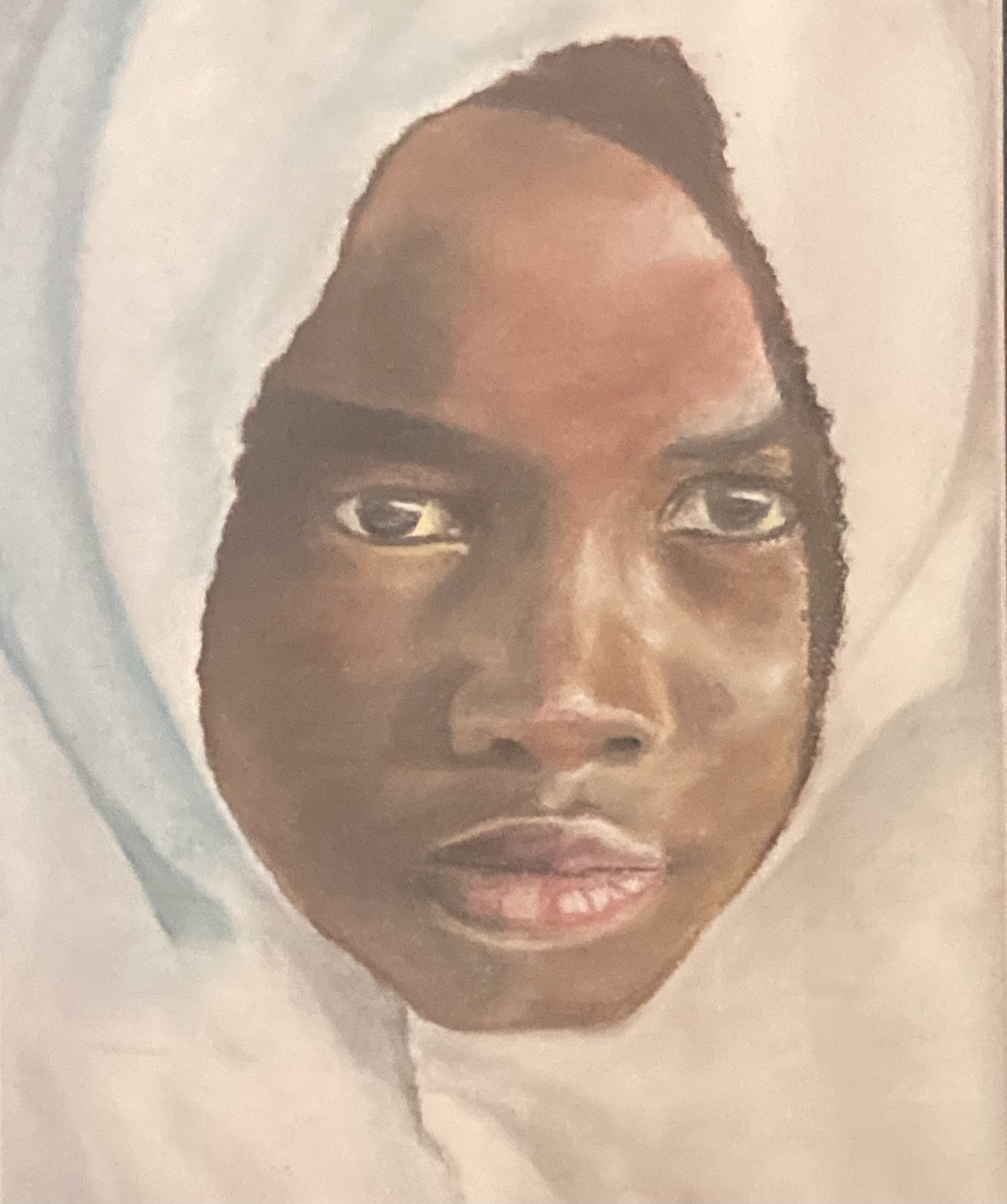

To my utter amazement, I wasn’t half bad! After practicing daily on nearly a thousand human faces using lead pencils, I yearned to add color. Pastel pencils and sticks were the answer. My focus broadened, first to rendering human skin tones with all their complex coloration, and then to the textures and hues of fur, feathers, scales, horns and hides of animals, wild and domestic.

I tried my hand at landscapes and found working en plein air to be exhilarating. Yet, nothing held my attention so much as the challenge of capturing some essence of other sentient beings. Bits of landscape have crept in anyway, as my animal portraits expanded from close-up mugshots to include the subjects’ habitats.

For several years I welcomed commission requests for portraits of any creature — grandkids to golden retrievers — and participated in a few gallery shows in Vermont and Florida. Mostly I sketched for my own amusement, portraying humans and other creatures who intrigue me. These included people I encountered working in Africa, or on a railroad trip across India; and a series of a dozen monkeys, apes and smaller primates at risk of extinction. With that Endangered Kin series, I can see now that my energies were being pulled towards the wild side.

Animal families. The arrival of COVID and the subsequent withdrawal from public life led to another focus change. I can’t remember exactly why, but early in the lockdown I started sketching animal families. These images of moms, and a few dads, with their young offspring felt so comforting. Life goes on in the animal kingdom, despite the travails of our species.

When I showed this slim portfolio to a few friends, it was suggested I turn it all into a kids’ book. Questions from one young viewer took the project in a new direction. “What are the animal babies’ names?” And then, “What are they talking about with their moms and dads?” I could think of only one way to find out: imagine. Sometimes we all can benefit from a sprinkling of magic.

When I attempted to answer questions about the family life of various creatures, the words came out as rhymes. And it seemed the rhymes wanted to be in the form of limericks. That humorous inclination was all too easy to follow. Somewhere in the process, I woke up my younger artist self from a long slumber. I needed his innocent imagination, youthful sense of mischief, and willingness to suspend disbelief. Boy, was he surprised with his older self!

Composing silly but meaningful verses turns out to be just as exciting and exasperating for me as sketching the family portraits they accompany. And that is how the book series Child of the Willd: Animal Families in Portraits and Poems took shape, with the first of five planned volumes published in the autumn of 2024.

In sum. With clarity gained over the years, another Picasso dictum rings true: It may take a long time to become young.

I am a work-in-progress in terms of reaching that goal. So far, the journey has been frequently frustrating, endlessly fascinating, and ultimately rewarding. I just wish my ten-year-old self had known that the best response to disappointment in art is to keep making marks until something interesting appears. Or take another piece of paper and start over. It sure helps not to be too judgmental. Guess it’s never too late to learn.